The Yemen crisis is again showing the world that wars do not end just because the fighting stops. They end when the political deals that caused them are fixed, or when those deals completely fail. In late 2025 and early 2026, Saudi airstrikes, land gains by the United Arab Emirates-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), and worse Saudi-UAE ties have brought back some of the biggest problems in Yemen’s war. This is happening at a time when global shipping routes, energy markets, and regional security are already weak. Yemen is again a local war with worldwide effects.

The most recent rise in tensions started at sea, in a way that was both symbolic and real. On December 30, 2025, Saudi warplanes attacked the port city of Mukalla in eastern Yemen. Riyadh said they were targeting a shipment of weapons from the United Arab Emirates, headed for separatist fighters in the south. Mukalla’s port, which faces the Gulf of Aden and is close to major shipping lanes, is important not only to Yemen but to the world economy.

The strike caused only minor damage, and no one was reported injured. However, it had a big political effect. It was the first time that Riyadh had attacked something connected to its Emirati partner in the anti-Houthi coalition. It also led the UAE to say that it would pull its remaining troops out of Yemen. A disagreement between two Gulf powers that had been building for a while suddenly became public.

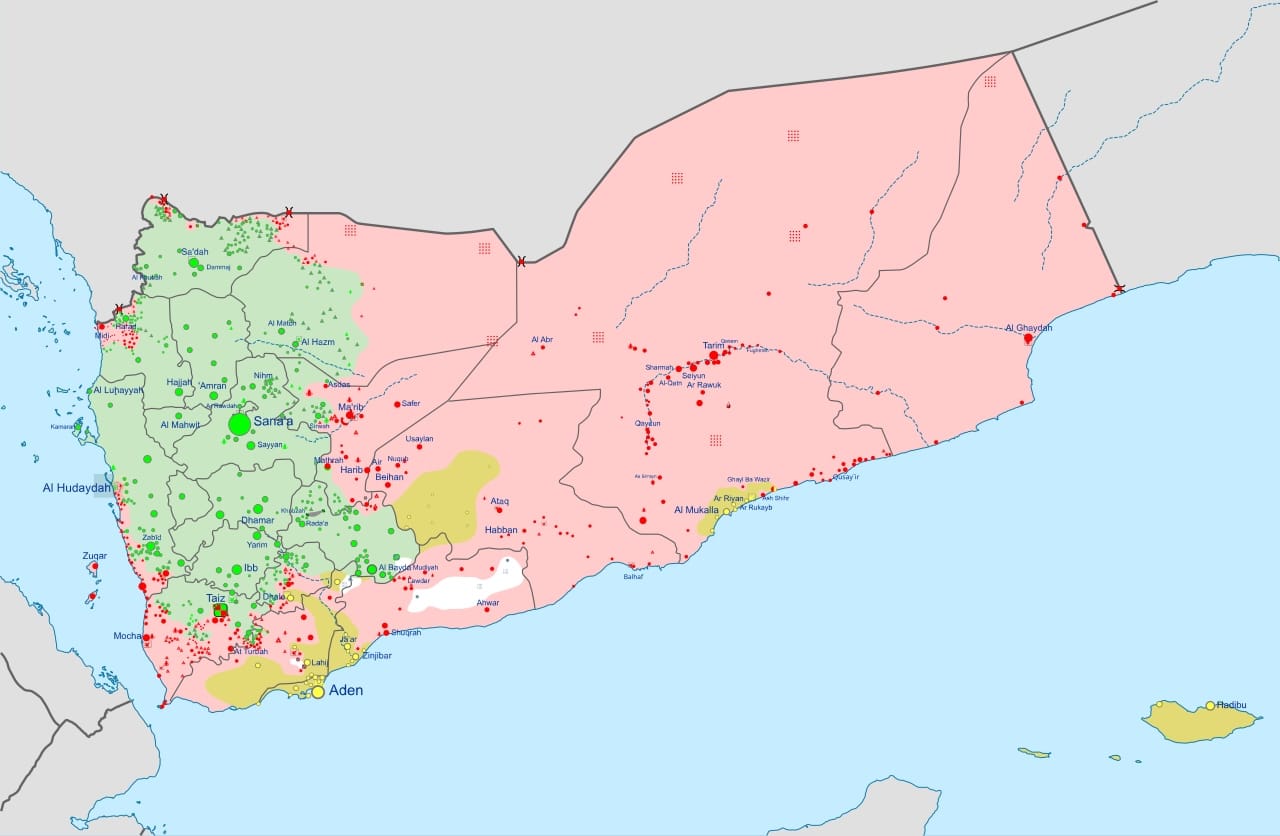

Map of Territorial Control in the Yemeni Civil War

Yemen is often simplified as just a conflict between “Houthis and everyone else,” but the situation is actually much more complex. The Houthi movement, which is supported by Iran and based in the northern highlands, is in control of Sanaa and most of Yemen’s most populated areas. The opposition is not a united group, but rather a mix of different forces: what is left of the official government, tribal groups, Islamist groups, and the STC (a southern separatist movement that has become very influential).

Since it was created in 2017, the STC has clearly stated its goal: to bring back an independent South Yemen with the borders it had before 1990. With strong support from the UAE in the form of training, weapons, and money, it has become the most important player in the south. Its leader, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, is also the vice president of Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council. This is a significant contradiction: the person who is supposed to help keep the country united is also the political leader of those who want to divide it.

In December 2025, the STC acted very quickly. It took control of large areas of Hadramout and Mahra in eastern Yemen. This included important oil sites, infrastructure, and a main border crossing with Oman. These gains were not just small local fights. Instead, they were the result of a slow change in power in the south. Hadramout is the biggest governorate in Yemen. It is home to PetroMasila, the country’s largest oil company. Its oil fields provide fuel and money to much of the south. The Hadramout Tribal Alliance, a tribal group supported by Saudi Arabia, briefly took control of the PetroMasila complex. They wanted a larger part of the local income. The STC took advantage of this situation.

It moved in and gained control. From there, its forces moved into Mahra. They secured a key crossing at the Omani border. This extended the STC’s power from the Arabian Sea to the eastern border. In Aden, units that supported the STC took over the presidential palace, the center of the Presidential Leadership Council. By the end of the year, the internationally recognised government was still officially in charge, but it had lost control of much of its territory.

The geographical representation of the war in Yemen underwent a transformation, mirroring a corresponding shift in the psychological landscape. For southern Yemenis, particularly those with recollections of the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, the advancements of the STC reflected a long-repressed desire. These developments, however, transgressed a critical threshold for Saudi Arabia. Riyadh has consistently perceived Yemen through the perspective of territorial integrity, favouring a central state that, despite its potential fragility, retains the capacity to negotiate boundaries, administer security, and impede adversarial entities, whether the Houthis or Al Qaeda, from exploiting Yemeni territory as a base against the kingdom.

Conversely, the UAE has demonstrated a greater inclination to bolster influential local stakeholders, notably those in control of ports, islands, and energy infrastructure, even if such support precipitates the de facto disintegration of Yemen. This discrepancy in strategic objectives, namely a centralised Yemen versus a more decentralised, fragmented south, has been evident since the commencement of the joint intervention in 2015. The novel aspect is the emergence of overt conflict as a result of this divergence.

As STC combatants strengthened their control in Hadramout and Mahra, Saudi Arabia increased its military involvement. Beyond the Mukalla strike, Saudi aircraft targeted STC‑affiliated forces in southern Yemen, including within Hadramout, an action that officials characterised as a “pre‑emptive” measure to avert disorder and dismantle destabilising encampments in proximity to the Saudi border. The Saudi‑supported National Shield Forces, a component of the coalition ostensibly opposing the Houthis, attempted to progress towards separatist camps, but encountered substantial opposition.

Key STC individuals, such as Ahmed bin Breik, publicly conceded that their unwillingness to retreat instigated the Saudi aerial assaults, implying that they perceive the conflict not as a simple miscommunication, but as a fundamental contest concerning the future of the south. Riyadh, conversely, has maintained that its operations do not represent “a declaration of war” against the STC, but rather a required action to forestall the kind of disunity that would render Yemen unmanageable.

On one plane, this constitutes a narrative of conflicting governmental objectives. On a more profound plane, it concerns the manner in which individuals and locales are ensnared in the conflict engendered by these objectives. Hadramout and Mahra are not merely entities in a geopolitical strategy; they represent societies whose inhabitants have observed external entities and internal armed forces negotiate over their resources even as fundamental amenities diminish.

When the Hadramout Tribal Alliance endeavoured to exert pressure on the central authority via the seizure of PetroMasila installations, it acted upon complaints pervasive throughout the Global South: “our petroleum is exported, yet our medical centres remain underfunded; our income dissipates, yet employment opportunities fail to materialise.” Subsequently, the STC exploited those identical regional complaints to legitimise its individual acquisition of power. In this regard, typical Yemenis undergo marginalisation on two occasions: initially, by a government that neglects to provide, and subsequently, by armed factions that assert to advocate for them, but incorporate their adversity into a more expansive geopolitical contest.

The strife in Yemen has consistently exhibited a binary nature, encompassing both a struggle for authority and a battle for respect. The Houthi insurgents’ descent from their northern territories in 2014, their capture of Sanaa, and the subsequent displacement of the globally acknowledged government, were facilitated by their leveraging of both systemic vulnerabilities and widespread public discontent regarding malfeasance and marginalisation. In 2015, Saudi Arabia and the UAE became involved, aiming to reinstate the existing government and counter Iranian influence.

This engendered a conflict that crippled Yemen’s economy, resulted in numerous casualties, internally displaced a substantial portion of the population, and instigated what the UN has frequently identified as one of the most severe humanitarian emergencies worldwide. Nevertheless, by 2022, and notwithstanding the extensive devastation, hostilities had de-escalated. A tacit accord between Riyadh and the Houthis led to a cessation of reciprocal incursions and Saudi aerial bombardments, and a reduction in armed conflict, although the political issues persisted. Despite the precariousness of the equilibrium, a considerable number of Yemenis, for the first time in many years, were able to envision a trajectory away from total warfare.

The emergent crisis in the southern region presents a risk of disrupting the delicate stability. As collaborative bonds among anti-Houthi factions disintegrate, the Houthis procure the singular advantage that has historically proven most effective: discord among their adversaries. Each day spent in conflict between Saudi-supported units and UAE-affiliated separatists represents a period in which Houthi leaders are afforded the opportunity to solidify their authority in the northern territories, augment their administrative oversight, and reinforce their established regional networks.

The ramifications extend beyond the borders of Yemen, given its coastline‘s proximity to the Bab el-Mandeb and the Gulf of Aden, both critical junctures in the network linking trade routes among Asia, the Gulf states, and Europe. Disruptions in this area are not merely hypothetical, as evidenced by Houthi assaults on maritime vessels in the Red Sea, which have already mandated deviations in shipping routes and elevated insurance expenditures. The anticipation of a concurrent conflict, pitting forces aligned with Saudi Arabia against those aligned with the Emirates along the same maritime corridor, introduces a supplementary dimension of jeopardy, a factor that has already been integrated into the economic models of oil traders and shipping enterprises.

As the philosopher Hannah Arendt once articulated, “political questions are far too serious to be left to the politicians.” The evolving situation in Yemen exemplifies this concept with acute clarity. What initiated as a domestic war has since transformed into a multifaceted conflict situated at the nexus of localised complaints, geopolitical competition, great‑power dynamics, and worldwide economic interconnectedness. Saudi Arabia perceives its national security as imperilled, especially with STC forces advancing toward its southern periphery, potentially disrupting supply routes.

The UAE regards its investments in southern ports, islands, and security alliances as central to its role as a maritime and logistical authority. Iran, observing from the periphery, gains from the disorder within the anti‑Houthi faction and the burden this crisis imposes on Gulf Cooperation Council cohesion. Amidst these circumstances, Yemeni citizens grapple with intensified aerial assaults, economic instability, and political ambiguity.

To truly understand what’s happening, we need to listen to more than just government officials and military experts. A shop owner in Mukalla, whose windows were broken in the December explosion, might not care if the shipment that was bombed had weapons or parts. What’s important to him is if people still shop at his store, if ships still arrive, and if insurance companies still cover his port. A farmer in Mahra, who sees STC trucks heading to the border of Oman, might not care as much about southern independence.

He might be more worried about more checkpoints and less money coming from families working in other countries because of new rules. A nurse in Aden, who works in a hospital that needs fuel from Hadramout to power its generators, might wonder if each new territory gained in the name of independence just makes life even more uncertain. These are real problems. They are the everyday costs of a war that has lasted over ten years.

Carl von Clausewitz famously said that “War is the continuation of politics by different methods.” In Yemen now, there’s a danger that the opposite is happening: politics is turning into a continuation of war through different methods, just a string of strategic actions without any clear idea of what peace could be like. Without that idea, every outside attack, land grab, and break in diplomatic relations just makes things worse.

For example, Saudi Arabia recently said that flights going to and from Aden must be checked in Jeddah, which the STC transport ministry saw as a punishment. This shows that airspace, like land and sea routes, is now something supposed partners use to gain an advantage. The worry is that every area (air, land, and sea) will become both militarised and politicised, leaving even less space for normal life.

What are the implications of inverting this rationale? The Syrian poet Adonis stated that “the homeland is not a suitcase, and one does not leave it at will.” The tragedy in Yemen is that millions have been compelled to treat their country as precisely that: a place to flee, rather than a place to build. For any substantive diplomatic process to take hold, external actors must initially acknowledge that Yemen is more than just a venue for their rivalries.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE possess legitimate security concerns; however, their pursuit of those concerns has frequently regarded Yemenis as instruments rather than agents. Reconceptualising Yemen as a political community, rather than a proxy battlefield, necessitates re-centring Yemeni voices in any negotiation regarding the future structure of the state, irrespective of whether that future is based on federalism, confederal arrangements, or a sequenced path toward self‑determination for the south.

Even now, there are chances to change how we see things. The decrease in major fighting since 2022 shows that violence can decrease when regional powers choose to be restrained. The STC currently has power because it controls much of the south. This power could be used for organised talks about self-rule within a larger agreement. Instead, it could be left to turn into a permanent division of land enforced by weapons.

Saudi Arabia has shown it can reach agreements with its enemies, like the Houthis, to stop attacks across borders. This ability could be used to seriously work with its partners, including the STC, on a political plan. This plan would recognise the south’s concerns while keeping a working Yemeni state. Such a plan will be hard to create, but the other choice is a long war of everyone against everyone.

For international policymakers and think tanks, addressing the Yemen crisis necessitates a dual-level approach. From a macro perspective, it constitutes a component of a wider contention regarding the future configuration of security in the Gulf and Red Sea, which bears implications for energy markets, shipping routes, and the orientation of regional powers. From a micro perspective, the issue revolves around the capacity of communities in Mukalla, Seiyun, Aden, and Al-Ghaydah to lead lives characterised by some degree of predictability and dignity.

These levels are interdependent. Devising maritime security frameworks intended to stabilise the Bab el-Mandeb without concurrently addressing the political fragmentation within Yemen is analogous to constructing a reinforced bridge on an unstable riverbank. Similarly, to concentrate exclusively on local power-sharing arrangements without considering how external rivalries influence incentives at the local level is to disregard the significant influence of regional politics.

As argued by the philosopher John Rawls, a just global system should acknowledge the “burdens of history” experienced by societies confronting adverse circumstances; Yemen is currently experiencing these burdens. Due to protracted underdevelopment, weak institutions, and external interference, the nation is particularly susceptible to the current unfolding crises. To transcend crisis management, any international response must consider Yemen as a political entity with the right to determine its trajectory, rather than simply a humanitarian emergency or a security concern.

This necessitates continuous support for comprehensive Yemeni dialogue, an adjustment of external military engagement, and economic strategies that target both immediate aid and the sustained reconstruction of state capabilities.

Ending Note

Ultimately, the central issue is not the triumph of Saudi Arabia or the UAE in southern Yemen, nor the sustained presence of the STC’s territorial control in its present state. Rather, the core concern is whether the Yemeni populace can regain the self-determination that has been diminished by a conflict in which numerous external actors have been involved. An important consideration for the international community lies in acknowledging, as the Lebanese intellectual Amin Maalouf has articulated, that “identity cannot be compartmentalised, you cannot divide it up into halves or thirds or cut it into segments.”

The multifaceted identity of Yemen encompassing northern and southern regions, tribal and urban communities, Zaydi and Sunni Muslims, coastal and highland populations cannot be readily divided through airstrikes or separatist encroachments. Any sustainable resolution should acknowledge this intricate nature and build upon it, instead of presuming it can be eradicated through military action or diplomatic negotiation.

Until such a resolution is achieved, the port of Mukalla will remain significant beyond its geographical coordinates, and Hadramout and Mahra will represent more than simply peripheral provinces in a remote conflict. They will serve as enduring reminders that, within a global framework where trade routes and security alliances intersect with vulnerable societies, the choices made by influential nations possess tangible consequences.

These reverberate in broken infrastructure, interrupted transportation, delayed compensation, and the private deliberations of families contemplating relocation. Policymakers face the responsibility of attending to these repercussions and, for once, permitting them to inform strategic planning, rather than suppressing them with the repetitive clamour of impending military operations.

Related Reads to Further Understand the Yemen Civil War

All the views and opinions expressed are those of the author. Image Credit: fahd sadi.

About the Author

Harshit Tokas holds a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU). He completed Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Amity University. He is a columnist for The Viyug.